A Step-by-Step Guide to the Hot Isostatic Pressing Diagram: 5 Key Stages for Flawless Material Densification

October 31, 2025

Abstract

Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) is a sophisticated manufacturing process that subjects components to elevated temperatures and high isostatic gas pressure in a sealed containment vessel. The primary objective of this procedure is the elimination of internal porosity and microporosity within materials, leading to the consolidation of powders or the densification of castings and additively manufactured parts. This results in a significant enhancement of the material's mechanical properties, such as fatigue strength, ductility, and fracture toughness. A hot isostatic pressing diagram serves as a graphical representation of the process cycle, plotting temperature and pressure against time. This diagram is fundamental for process control, illustrating the critical stages of heating, pressurization, soaking at peak parameters, and controlled cooling. Understanding the nuances of each stage as depicted on the diagram is essential for tailoring the cycle to specific materials—from superalloys and ceramics to advanced composites—thereby ensuring the final component achieves its full theoretical density and desired microstructural characteristics without defects.

Key Takeaways

- A hot isostatic pressing diagram maps the entire cycle of temperature and pressure over time.

- The main goal is to eliminate internal voids, achieving nearly 100% material density.

- Key stages include heating, pressurization, soaking, and controlled cooling for optimal results.

- Isostatic pressure from an inert gas, like argon, ensures uniform densification from all directions.

- Post-HIP analysis is vital to verify the integrity and properties of the final component.

- The process significantly improves the mechanical performance of critical, high-stress parts.

- Understanding the diagram allows for precise control over the material's final microstructure.

Table of Contents

- An Introduction to Hot Isostatic Pressing: The Art of Forging Perfection

- Stage 1: The Preparatory Phase – Loading and Sealing

- Stage 2: The Ascent – Evacuation, Heating, and Pressurization

- Stage 3: The Peak – Soaking for Full Densification

- Stage 4: The Descent – Controlled Cooling and Depressurization

- Stage 5: The Aftermath – Post-HIP Evaluation and Analysis

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Conclusion

- References

An Introduction to Hot Isostatic Pressing: The Art of Forging Perfection

Before we can properly dissect the intricacies of a hot isostatic pressing diagram, we must first build a solid foundation of understanding. What is this process, and why has it become so fundamental in the creation of high-performance materials? Think of it not merely as a manufacturing step, but as a transformative journey for a material, taking it from a state of imperfection, riddled with tiny internal voids, to a state of near-perfect solidity and strength.

What is Hot Isostatic Pressing? A Foundational Understanding

At its core, Hot Isostatic Pressing, often abbreviated as HIP, is a heat treatment process that combines three key elements: extremely high temperature, immense pressure, and an inert atmosphere. A component or a collection of powder is placed inside a sealed, high-pressure containment vessel. The vessel is then heated to a high temperature, typically up to 2,000°C (3,632°F), a point where the material becomes soft and more plastic. Simultaneously, the vessel is filled with an inert gas, most commonly argon, and pressurized to levels that can exceed 200 megapascals (MPa), or about 30,000 pounds per square inch (psi).

The "isostatic" part of the name is the key. Unlike conventional pressing, which applies force in one direction (uniaxially), isostatic pressure is uniform from all directions. Imagine submerging an object deep in the ocean; the water pressure acts on its entire surface equally. The inert gas in a HIP vessel behaves in the same way, squeezing the component from every possible angle. This uniform pressure ensures that internal pores and voids collapse and weld shut on a microscopic level, without distorting the overall shape of the part. The combination of heat, which makes the material malleable, and pressure, which provides the driving force for closure, is what enables this remarkable transformation.

The "Why": Eliminating Porosity and Enhancing Material Properties

The primary reason for employing the HIP process is the elimination of porosity. Porosity refers to the small, empty spaces or voids within a solid material. These voids can be remnants from the casting process, gaps between particles in powder metallurgy, or tiny imperfections formed during additive manufacturing (3D printing). From a mechanical standpoint, these pores are incredibly detrimental. They act as stress concentrators, meaning that when a force is applied to the component, the stress becomes magnified at the edges of these voids. This makes the material significantly weaker and more prone to cracking and failure, particularly under cyclic loading, which leads to fatigue.

By subjecting a part to the HIP process, these internal voids are permanently closed. The material diffuses across the void boundaries under the influence of heat and pressure, effectively healing the defect from the inside out. The result is a component with a density that approaches 100% of its theoretical maximum. This densification brings about a cascade of improvements in mechanical properties:

- Increased Ductility: The material can deform more under stress before fracturing.

- Enhanced Fatigue Life: The absence of stress-concentrating pores means the component can withstand many more cycles of loading and unloading.

- Improved Fracture Toughness: The material is more resistant to the propagation of cracks.

- Greater Consistency: Properties become more uniform throughout the component, eliminating weak spots.

These improvements are not just marginal; they can be transformative, allowing engineers to design lighter, more reliable parts that can operate under more extreme conditions. This is why HIP is indispensable in industries like aerospace, medical implants, and energy, where material failure is not an option.

A Historical Perspective: From Nuclear Reactors to Aerospace Marvels

The concept of hot isostatic pressing was not born in a vacuum. It was developed in the mid-1950s at the Battelle Memorial Institute in Columbus, Ohio, USA. The initial motivation was to clad nuclear fuel elements for experimental gas-cooled reactors (Atkinson & Davies, 2000). The challenge was to achieve a perfect, diffusion-bonded seal between the uranium fuel and its protective cladding material. Researchers discovered that applying high-pressure gas at an elevated temperature was a uniquely effective way to accomplish this.

From these specific origins in the nuclear industry, the potential of the technology quickly became apparent to other fields. The aerospace industry, in its perpetual quest for materials with higher strength-to-weight ratios, was an early adopter. HIP was used to heal defects in superalloy castings for jet engine turbine blades, a practice that continues to be standard today. It allowed for the creation of complex, near-net-shape components from metal powders, reducing waste and costly machining operations. As we look around in 2025, the applications have expanded dramatically, touching everything from the ceramic components in our electronics to the titanium hip implants that improve human lives, all thanks to this powerful method of material refinement.

Stage 1: The Preparatory Phase – Loading and Sealing

The journey through the hot isostatic pressing diagram begins long before the heat and pressure are applied. The preparatory stage is one of meticulous care and precision, as any error introduced here can compromise the entire process. Success in HIP is built upon a foundation of cleanliness, proper arrangement, and a perfect seal against the outside world.

Meticulous Loading: The First Step to a Flawless Component

The first physical action is loading the components into the HIP vessel's workload basket. This is not a random placement. Parts must be arranged to allow for uniform gas flow and heat transfer. If components are packed too tightly or touch one another, it can create "shadow" areas where the temperature or pressure application is less effective, leading to incomplete densification in those regions. Spacers made of ceramic or compatible metals are often used to ensure adequate separation.

Furthermore, the components and the interior of the vessel must be scrupulously clean. Any contaminants, such as oils, greases, or even microscopic dust particles, can vaporize at high temperatures. These vaporized substances can interfere with the diffusion bonding process that closes the pores or, in a worst-case scenario, react with the component's material, leading to surface defects or undesirable changes in chemistry. The principle here is simple: you can only achieve a pure, dense material if you start with a pure environment.

Encapsulation: Creating a Barrier for Powder Metallurgy

The HIP process can be applied to two main categories of materials: pre-existing solid parts (like castings) that need densification, and metal or ceramic powders that need to be consolidated into a solid part. For powders, an additional preparatory step is required: encapsulation.

Since the powder particles have no inherent structural integrity, they must be contained within a sealed can or capsule. This capsule is typically made from a ductile metal like mild steel or stainless steel. The capsule is designed to be the approximate final shape of the desired component, a concept known as "near-net-shape" manufacturing. The powder is loaded into this capsule, which is then vibrated to ensure the powder is packed as densely as possible to start with.

After filling, the capsule is evacuated to remove any trapped air and then hermetically sealed, usually by welding. This sealed capsule now acts as a pressure-tight barrier. During the HIP cycle, the high-pressure inert gas will squeeze the outside of the capsule, and the capsule, in turn, will deform and transmit that isostatic pressure uniformly to the powder within, consolidating it into a fully dense solid. After the HIP cycle is complete, this capsule is removed, typically through chemical etching or machining, to reveal the finished part.

The Significance of a Perfect Seal

Whether dealing with a solid component or an encapsulated powder, the integrity of the HIP vessel's seal is paramount. The vessel itself is a marvel of engineering, designed to withstand immense internal forces. The main closure, or lid, is secured with a robust frame or threaded system. A high-integrity seal prevents the costly and high-purity inert gas from escaping.

More importantly, it prevents atmospheric gases, particularly oxygen and nitrogen, from entering the vessel. At the high temperatures of the HIP process, many advanced materials, like titanium alloys and superalloys, are highly reactive. Exposure to even trace amounts of oxygen can lead to the formation of brittle oxide layers on the surface or within the material, severely degrading its mechanical properties. The perfect seal ensures that the component is bathed only in the inert gas, preserving its chemical integrity throughout the densification journey.

Stage 2: The Ascent – Evacuation, Heating, and Pressurization

With the components securely loaded and the vessel sealed, the active part of the process begins. This phase is characterized by a controlled ascent in both temperature and pressure. How this ascent is managed is critical to the outcome and is clearly visualized on the y-axes (Temperature and Pressure) against the x-axis (Time) of a hot isostatic pressing diagram.

Creating a Vacuum: The Removal of Atmospheric Impurities

Before heating begins in earnest, the sealed vessel undergoes an initial evacuation cycle. A powerful vacuum pump is used to remove the air that was inside the vessel when it was sealed. The purpose, as with the initial cleaning, is to eliminate contaminants. The primary culprits are oxygen and water vapor. Removing them at the start prevents them from reacting with the hot components later in the cycle. This step ensures that the atmosphere inside the HIP unit is as pure as possible before the inert gas is introduced. On the hot isostatic pressing diagram, this might appear as a brief, initial phase at ambient temperature where the internal pressure drops to a near-vacuum.

The Heating and Pressurization Ramp: A Controlled Rise

Once the vacuum is established, the heating and pressurization stages commence. These two parameters are often increased concurrently, though the exact profile depends on the material and the specific HIP unit's capabilities.

The temperature is increased by powerful heating elements located inside the pressure vessel. The rate of this temperature increase, or "heating ramp," is carefully controlled. Ramping up the temperature too quickly can induce thermal shock in brittle materials like ceramics, causing them to crack. For large components, a slower ramp is necessary to ensure the entire part heats up uniformly, from its core to its surface. The goal is to reach the target "soak" temperature without introducing new stresses into the material.

Simultaneously, the inert gas is pumped into the vessel, causing the pressure to rise. The rate of pressurization is also controlled. Visualized on the diagram, you would see two curves rising over time: one for temperature and one for pressure. The shape of these curves—whether they are linear, stepped, or curved—is a key part of the process recipe.

Comparison of Common Inert Gases in HIP

The choice of inert gas is a practical consideration based on the required temperature and cost. Argon is the most common choice due to its inertness and availability, but nitrogen can also be used for certain materials where nitriding is not a concern.

| Feature | Argon (Ar) | Nitrogen (N₂) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Reactivity | Extremely low; inert with virtually all materials. | Low, but can form nitrides with some reactive metals (e.g., Titanium) at high temperatures. |

| Operating Temperature | Suitable for the highest temperatures, up to and beyond 2000°C. | Generally used for lower temperature applications (< 1400°C) to avoid reactions. |

| Cost | More expensive. | Less expensive than Argon. |

| Purity Requirements | High purity (99.995% or better) is essential for sensitive alloys. | Purity is also important, but requirements can sometimes be slightly less stringent. |

| Typical Applications | Superalloys, titanium, medical implants, advanced ceramics, powder metals. | Tool steels, some stainless steels, densification of certain castings where nitriding is not an issue. |

Understanding these differences allows process engineers to select the most appropriate and cost-effective gas for a given application, which is a crucial decision in the overall HIP cycle design.

Stage 3: The Peak – Soaking for Full Densification

After the controlled ascent, the process reaches its zenith. This is the "soak" or "hold" period, where the temperature and pressure are held constant at their maximum values for a predetermined amount of time. This stage is the heart of the HIP process; it is where the real work of densification occurs. On the hot isostatic pressing diagram, this phase is represented by a distinct plateau in both the temperature and pressure curves.

The Interplay of Pressure, Temperature, and Time

The three critical parameters of the soak period are temperature, pressure, and time. They are not independent variables; they work in concert to close the material's internal porosity.

- Temperature: The high temperature serves to lower the material's yield strength. It makes the material "softer" and more plastic, allowing it to deform and flow under pressure. Importantly, it also dramatically increases the rate of atomic diffusion, which is the movement of atoms within the solid material.

- Pressure: The high isostatic pressure provides the driving force for densification. It creates a stress state within the material that exceeds its high-temperature yield strength, causing the material around a pore to collapse inward.

- Time: The hold time must be sufficient for the densification mechanisms to go to completion. Closing a large pore is not instantaneous; it requires time for the material to creep and for atoms to diffuse across the void to create a solid bond.

The selection of these three parameters is a careful balancing act. A higher temperature or higher pressure might reduce the required hold time, but could also lead to unwanted effects like excessive grain growth, which can make the material more brittle (Nishida, 2011). The goal is to find the optimal combination that achieves full density while preserving or even enhancing the material's desired microstructure.

The Mechanisms of Pore Closure

During the soak period, several physical mechanisms work together to eliminate voids. The process can be thought of as a sequence.

- Plastic Yielding: Initially, for larger pores, the material surrounding the void behaves like a thick-walled pressure vessel under external pressure. The applied isostatic pressure causes the material to plastically deform and collapse inward, rapidly shrinking the size of the pore. This is the dominant mechanism at the beginning of the soak period.

- Power-Law Creep: As the pores become smaller, the stress concentrations decrease, and plastic yielding becomes less effective. The dominant mechanism then shifts to creep, which is the slow, time-dependent deformation of a material under stress at high temperature. The material slowly "creeps" into the remaining void space.

- Diffusion: In the final stage, when only very small, isolated micropores remain, the primary mechanism is diffusion. Individual atoms migrate from the surface of the pore into the bulk material, or across the pore to the opposite surface, effectively "filling in" the hole atom by atom. This process creates a perfect metallurgical bond, leaving no trace of the original defect.

Thinking about this progression helps to understand why the hold time is so important. While plastic yielding is fast, creep and diffusion are much slower processes. The soak period must be long enough for these slower mechanisms to completely eliminate even the smallest voids.

Parameter Effects in Hot Isostatic Pressing

The precise values chosen for the soak period have a direct and predictable impact on the final material. Engineers use this knowledge, often encapsulated in processing maps, to tailor the HIP cycle.

| Parameter | Effect on Microstructure | Effect on Process |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Higher temps increase diffusion and creep rates, but can cause excessive grain growth, degrading some mechanical properties. | Reduces required hold time but increases energy costs and wear on the furnace components. |

| Pressure | Higher pressure increases the driving force for plastic yielding and creep, aiding in the closure of larger pores. | Reduces required time but requires a more robust (and expensive) pressure vessel. |

| Time | Longer hold times ensure complete diffusion bonding and closure of all pores. | Increases cycle time and cost; excessive time at temperature can lead to grain growth. |

This table illustrates the trade-offs involved. Crafting the perfect hot isostatic pressing diagram for a new alloy or component often involves a series of experiments to find the "sweet spot" that balances full densification, optimal microstructure, and economic efficiency.

Stage 4: The Descent – Controlled Cooling and Depressurization

Once the soak period has successfully concluded and the material has reached its full density, the component cannot simply be removed from the furnace. The descent from peak temperature and pressure is a stage just as critical as the ascent and soak. An uncontrolled descent can undo the benefits gained or introduce entirely new defects. This phase is represented on the hot isostatic pressing diagram by the downward-sloping curves for temperature and pressure.

The Cooling Phase: Managing Microstructure and Preventing Thermal Shock

The rate at which the component is cooled is perhaps the single most important variable in this stage. The cooling rate directly influences the final microstructure of the material, which in turn dictates its mechanical properties. Modern HIP systems offer a range of cooling rates, from very slow furnace cooling to extremely fast, uniform rapid quenching (URQ).

- Slow Cooling: In some cases, a slow, controlled cooling rate is desired. This allows the microstructure to remain stable and minimizes the buildup of internal residual stresses. For some alloys, slow cooling is necessary to achieve a specific phase transformation or precipitation state.

- Rapid Quenching: In many other applications, particularly for superalloys and certain steels, rapid cooling is beneficial. By cooling the component very quickly from the HIP temperature, it is possible to lock in a desirable high-temperature microstructure or to perform a solution heat treatment simultaneously with the HIP cycle. This can eliminate the need for a separate, subsequent heat treatment step, saving significant time and money (Fujikawa, 2017). A key benefit of modern HIP technology is the ability to cool parts quickly and uniformly, preventing the distortion or cracking that can occur with traditional liquid quenching.

The danger of improper cooling is thermal shock. If a component, especially a large one or one made of a brittle material like a ceramic, is cooled too quickly or non-uniformly, the surface will contract faster than the core. This differential shrinkage creates immense internal stresses that can cause the part to warp or even crack. Therefore, the cooling portion of the hot isostatic pressing diagram is carefully engineered to match the material's thermal properties and the desired final microstructure.

Depressurization: A Careful Release of Force

Concurrent with or following the cooling phase, the pressure in the vessel is reduced. The high-pressure inert gas is carefully vented from the system, gradually returning the vessel to atmospheric pressure. This process is generally more straightforward than temperature control, but it must be done in a controlled manner. A sudden depressurization could potentially damage the vessel's components or, in the case of a component with any remaining surface-connected porosity, cause issues. However, since the goal of HIP is to eliminate all porosity, this is typically not a concern for the component itself. By the time depressurization occurs, the part is a fully dense solid, and the external pressure can be removed without affecting its newly perfected internal structure.

On the diagram, the pressure curve will slope downwards, typically reaching atmospheric pressure before the component has fully cooled to room temperature. This allows the vessel to be opened once it is safe to do so from a temperature perspective.

Stage 5: The Aftermath – Post-HIP Evaluation and Analysis

The journey depicted on the hot isostatic pressing diagram concludes when the cycle ends, but the work is not yet finished. The final stage is one of verification. Having subjected a component to such an advanced and costly process, it is absolutely essential to confirm that the desired outcome was achieved. This involves removing the part, performing any necessary finishing steps, and conducting a battery of tests to ensure it meets the stringent quality standards required.

Unloading and De-canning: Revealing the Final Product

Once the vessel has cooled to a safe temperature and has been depressurized, the main closure can be opened and the workload basket can be removed. The components are then carefully unloaded.

For parts that were consolidated from powder, an additional step is required: de-canning. The metal capsule that contained the powder during the HIP cycle must be removed. This is often done through chemical milling, where the entire encapsulated part is submerged in an acid bath that selectively dissolves the capsule material (e.g., mild steel) without affecting the final component material (e.g., a nickel superalloy). In other cases, the capsule may be removed through precision machining. What is revealed is a fully dense, near-net-shape component that perfectly mirrors the internal cavity of the original capsule.

The Indispensable Role of Quality Control

Quality control (QC) is not an optional extra; it is an integral part of the HIP process chain. For components used in critical applications like jet engines, power plant turbines, or surgical implants, failure could have catastrophic consequences. Therefore, 100% inspection is often the rule. This inspection process uses a variety of techniques to confirm two main things: first, that the part is free of any internal defects, and second, that it possesses the required mechanical and microstructural properties.

Verifying Densification with Non-Destructive Testing (NDT)

Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) methods are used to inspect the interior of a component without damaging it. The most common technique used for post-HIP evaluation is ultrasonic testing. In this method, high-frequency sound waves are sent into the component. If the part is fully dense, the sound waves will travel through it predictably. If there are any remaining voids or inclusions, the sound waves will reflect off these defects, creating an echo that can be detected by a sensor. By scanning the entire part, a 3D map of its internal structure can be created, providing definitive proof of full densification. Other NDT methods like X-ray or CT scanning may also be used for certain applications.

Characterizing Material Integrity with FTIR Spectroscopy

Beyond simply checking for voids, a deeper analysis is often required to confirm the material's chemical and structural integrity. This is where analytical techniques like Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy can play a subtle but important role. While FTIR is more commonly associated with polymers and organic materials, it has specific applications in the context of HIP.

For instance, in powder metallurgy, organic binders are sometimes used to help shape the powder before it is placed in the capsule. It is critical that these binders are fully burned out before the capsule is sealed, as any residual organic material can lead to carbon contamination and porosity during the HIP cycle. FTIR spectroscopy is an excellent tool for analyzing the pre-HIP powder to confirm the complete removal of these binders.

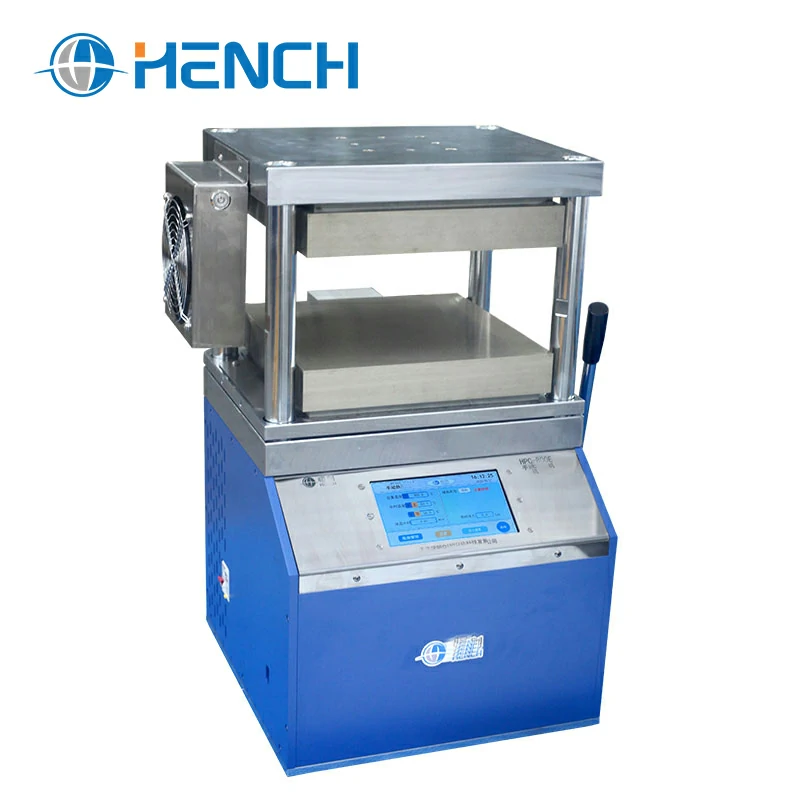

Similarly, for advanced ceramic matrix composites (CMCs) or polymer-derived ceramics processed via HIP, FTIR can be used to analyze the final material. It can verify the chemical bonding structure, confirm the completion of desired chemical reactions, and detect the presence of unwanted phases or impurities (Eom et al., 2013). Preparing a solid sample for this type of transmission analysis often requires creating a thin, transparent pellet. This is typically done by grinding a small amount of the sample with potassium bromide (KBr) powder and then using specialized sample preparation equipment to press the mixture into a high-quality pellet under high force. The quality of this preparation is directly linked to the quality of the resulting spectrum. High-performance hydraulic laboratory presses ensure that the KBr pellet is uniform and free of imperfections, leading to clear and reliable analytical results that give confidence in the quality of the HIP-processed material.

In essence, while the hot isostatic pressing diagram charts the physical journey of densification, these advanced analytical techniques provide the chemical and structural confirmation that the journey was a success.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main purpose of a hot isostatic pressing diagram?

A hot isostatic pressing diagram is a process control tool. Its primary purpose is to provide a clear, graphical representation of the temperature and pressure applied to a component over the entire duration of the HIP cycle. It allows engineers to design, execute, and replicate the exact conditions needed to achieve full densification and the desired microstructure for a specific material.

What types of materials are commonly processed using HIP?

A wide variety of materials benefit from HIP. These include nickel-based and cobalt-based superalloys for aerospace and industrial gas turbines, titanium alloys for aerospace and medical implants, tool steels and high-speed steels for cutting applications, advanced ceramics like silicon nitride and alumina, and various metal matrix and ceramic matrix composites. It is also a fundamental process in powder metallurgy for creating fully dense parts from powders.

Can HIP remove all types of defects?

HIP is extremely effective at removing internal defects that are not connected to the surface, such as gas porosity, shrinkage cavities, and voids between powder particles. However, it cannot heal surface-connected cracks or voids, because the high-pressure gas will penetrate these openings, meaning there is no pressure differential to force the defect closed. It also cannot remove solid inclusions, like bits of ceramic from a casting mold, although it will bond the matrix material perfectly around the inclusion.

How does the pressure in HIP differ from other pressing methods?

The key difference is the "isostatic" nature of the pressure. In conventional forging or uniaxial pressing, force is applied along a single axis. This can effectively consolidate a material but may also distort its shape and can lead to non-uniform density. In HIP, the inert gas applies equal pressure from all directions simultaneously. This ensures that the component densifies uniformly without changing its overall geometric shape, which is ideal for complex, near-net-shape parts.

What is the role of the inert gas in the HIP process?

The inert gas, typically argon, serves two critical functions. First, it is the medium that transmits the high pressure to the component. As a gas, it can conform to any shape, ensuring the pressure is truly isostatic. Second, it provides a protective atmosphere. Being chemically inert, it prevents the hot component from reacting with oxygen or other atmospheric contaminants, which would otherwise degrade the material's properties.

How long does a typical HIP cycle take?

The duration of a HIP cycle can vary significantly depending on the material, the size of the components, and the specific parameters of the hot isostatic pressing diagram. A cycle can be as short as a few hours for small components or simple densification, or it can last for over 24 hours for very large parts or complex powder consolidation cycles that require long heating, soaking, and cooling periods.

Is HIP an expensive process?

Yes, hot isostatic pressing is generally considered a high-cost manufacturing process. The equipment itself—the high-pressure vessel, furnace, and control systems—represents a significant capital investment. Additionally, the process consumes a large amount of energy and uses expensive, high-purity inert gas. For these reasons, HIP is typically reserved for high-performance components where the significant improvement in material properties and reliability justifies the cost.

Conclusion

The hot isostatic pressing diagram is more than just a graph; it is the blueprint for perfection in materials science. It charts a transformative path from a state of inherent imperfection to one of near-flawless integrity. By carefully orchestrating the interplay of temperature, pressure, and time, the HIP process heals materials from the inside out, closing the hidden voids that compromise strength and reliability. Each stage, from the meticulous preparation and loading to the controlled ascent, the critical soak at peak conditions, and the carefully managed descent, plays a vital role in the final outcome. Understanding this journey, as visualized on the diagram, empowers engineers and scientists to push the boundaries of material performance. The process allows for the creation of components that are stronger, last longer, and operate more safely in the most demanding environments imaginable, from the depths of the earth to the farthest reaches of the sky. The synergy between this powerful consolidation technique and precise post-process analytical methods ensures that the promise of the diagram is realized in a tangible, reliable, and superior final product.

References

Atkinson, H. V., & Davies, S. (2000). Fundamental aspects of hot isostatic pressing: An overview. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, 31(12), 2981–3000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-000-0078-2

Eom, J. H., Kim, Y. W., & Song, I. H. (2013). Effect of hot pressing on the microstructure and mechanical properties of polymer-derived SiC-based ceramics. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 33(10), 1663–1669.

Fujikawa, S. (2017). Recent trends in hot isostatic press systems. KOBELCO Technology Review, 35, 46-53.

Nishida, M. (2011). Effect of HIP treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of investment cast TiAl alloys. Journal of the Japan Society of Powder and Powder Metallurgy, 58(5), 311-316.